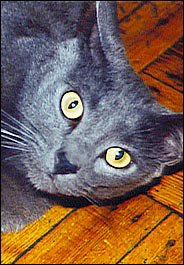

A Manhattan Court to Rely Upon an 1894 Dog Law in Order to Decide Custody of a Russian Blue Named Oliver Gatsby

|

| Oliver Gatsby |

A female attorney adopts a pure-bred Russian Blue cat from an animal rescue group. She begins caring for him and they become close. Almost a year later the cat's previous owner locates her and files papers against her demanding its return. So, who owns the cat?

That is the issue which the New York State Supreme Court in Manhattan will decide later this month. Amazingly enough, there does not appear to be much in the way of legal precedent for the court to go on in spite of the fact that lost cats are a common enough occurrence.

For instance, millions of cats and dogs are adopted each year from shelters and rescue groups without either party knowing where the animal came from or who previously owned it. Likewise, caring people take in countless animals from the street every day. Most likely the difficulty involved in tracking down lost pets accounts for the dearth of litigation in this area.

The Manhattan case had its genesis in Missouri in 2000 when aspiring poet Chavisa Woods, then 19, scooped up off the street a six-month-old Russian Blue kitten who had been cruelly thrown from a car. She named him Oliver and began caring for him and treating his chronic urinary tract infections.

Woods and Oliver moved to Manhattan in 2003 and all was well until the cat slipped out of her Lower East Side walk-up in September 2004. Oliver was rescued from the street by an unidentified person who promptly turned him over to KittyKind, a feline rescue group which operates out of Petco's Union Square store. He was put up for adoption and immediately claimed by a female attorney who renamed him Gatsby.

Woods somehow managed to track Oliver Gatsby to KittyKind but when she demanded that the group turn over to her the name and address of the cat's new caregiver KittyKind refused and Woods sought relief in the courts. For its part, KittyKind did not contact the lawyer, now proceeding under le nom de guerre of Jane Doe, until it had already lost the case and was ordered to do so by the court. By that time Jane Doe had been caring for Oliver Gatsby for almost a year and refused to part with him.

In early December, New York State Supreme Court Justice Marylin G. Diamond ruled that the case was governed by section seven of the New York City Dog License Law of 1894 which gives owners of lawfully seized pets only forty-eight hours to reclaim them. Recognizing however that more than one-hundred non-profit groups participate in the Mayor's Alliance for N.Y.C. Animals and that these organizations often subcontract with private individuals to rescue and foster lost and homeless pets, Diamond reasoned that it would be practically impossible for pet owners to locate lost pets unless they were listed on the Animal Care and Control (ACC) register. She therefore ruled that the forty-eight-hour rule did not come into effect until the lost pet had been listed on the register.

Based on this preliminary ruling, the legal issues to be settled at a trial scheduled to begin on January 19th are as follows: When and if did KittyKind list Oliver Gatsby with the ACC? And, when did Woods effectively assert her claim?

|

| Some of the Cats Removed from Marlene Kess's House |

Press reports in the New York Law Journal, The New York Times, and the New York Daily News strongly suggest that answering those two questions conclusively will not be easy. Diamond has therefore raised the possibility that she may not limit a pet owner's right to reclaim a lost animal to the filing of a notice with the ACC.

The defense is expected to assert at trial not only that Oliver Gatsby is happy and well cared for by his new guardian but that Woods, now working in a wine shop in upstate Hudson, New York, is an unfit owner because she was out of town when a blind roommate allowed the cat to escape into the street. People considering adopting a cat or a dog are closely monitoring this case as are animal rescue groups.

Unless the court delineates some clear guidelines to be followed in cases like this, new pet owners and shelters could find themselves subjected to protracted litigation. Down the road it is likely that legislative action will be needed in order to deal with situations like these because the 1894 law which Diamond is relying upon has severe limitations.

Although it is difficult to predict how this case will turn out, Diamond's willingness to expand the inquiry beyond the formal reach of the 1894 statute demonstrates that she is sympathetic to the plaintiff's suit. It is also conceivable that, depending upon the personalities involved, the court might award joint custody of the cat or at least grant the loser visitation rights as it is sometimes done when pets are contested in divorce proceedings.

Since cats neither like to travel nor to have visitors this would not be in the best interests of Oliver Gatsby. The fact that KittyKind figures so prominently in this matter makes it highly likely that its rescue and adoption procedures will come under scrutiny at the upcoming trial and this may also lessen Jane Doe's chances of success.

The organization's founder, Marlene Kess, was caught last May with forty-eight live cats and more than two-hundred dead ones at her East Orange, New Jersey residence. (See Cat Defender post of May 26, 2005 entitled "Cat Hoarder Masquerading as Cat Savior Kills More Than 200 Cats.")

Compounding matters further, the SPCA caught her again in August hoarding more cats; this time around she was in possession of more than one-hundred cats. She is currently appealing a slap-on-the-wrists sentence of twenty-one days in the stir, a modest fine of $14,099, and a requirement that she perform three years of community service; that appeal is scheduled to be heard January 20th before Essex County Superior Court Judge Nancy Sevilli in Newark. Furthermore, it is likely that the SPCA will file additional charges stemming from the August raid upon her home.

It is stupefying that neither Petco nor animal control personnel in New York have acted to remove Kess from the management of KittyKind and to bar her from owning any more cats as officials in Virginia have done in the case of Ruth Knueven. (See Cat Defender post of December 23, 2005 entitled "Virginia Cat Hoarder Who Killed 221 Cats and Kept Another 354 in Abominable Conditions Gets Off With $500 Fine.")

More to the point, cat lovers can only hope and pray that Kess's community service does not entail working with cats.

Photos: Chavisa Woods (Oliver Gatsby) and Mike Derer of the Associated Press (Kess's cats).

<< Home